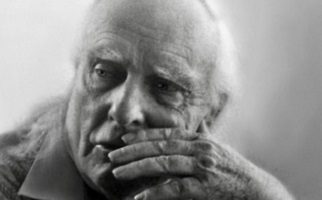

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) was born in Vienna, Austria, on April 26, 1889. The son of a wealthy family, he joined the Techinsche Hochschule in Berlin in 1906. In 1908 he entered the University of Manchester to study aeronautical engineering. He soon surrendered, and under the influence of Gottlob Frege, German mathematician and philosopher and one of the creators of modern logic, he enrolled in the course of the British philosopher Bertrand Russell, at Trinity College in Cambridge. In 1913 he moved to Norway, where he studied logic.

In 1914, when World War I broke out, he enlisted as a volunteer in the Austrian army and was sent to the front in Russia and Italy. In 1918 he was injured and arrested by the Italians and was only released in 1919. At that time, he wrote the outline of his main work, the result of his discussions with Russell, entitled “Logical-Philosophical Treaty”.

In 1919, after the death of his father, he resigned his inheritance and assumed the position of teacher in a small primary school in Lower Austria. At that time, he developed a spelling dictionary for early childhood education. In 1921 he published “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” (Logical-Philosophical Treaty) in German and the following year he translated it into English. In 1926, due to his strict style, showing little patience with children who could not follow his reasoning, the parents of the students asked him to leave school. He then worked as a gardener in a monastery near Vienna.

His return to philosophy is gradual. In 1924 he began contacting the members of the so-called Circle of Viana, which founded the philosophical system called Positivism. In 1929, under the influence of Frank P. Ramsey, a student of mathematics and philosophy, he decided to return to the University of Cambridge. That same year he received his doctorate, presenting his own “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” as a thesis, under the direction of Ramsey. From 1930 he began teaching at the same university.

In the context of his discussions with the Circle of Viana, Ludwig Wittgenstein gradually observes serious errors and misunderstandings in his first work, and begins to write “The Philosophical Investigations”, published posthumously in 1953, in a German / English bilingual edition.

In 1939, Ludwig Witttgenstein became naturalized as a British citizen. During World War II (1939-1945) he volunteered for health services and worked at the Guy Hospital. Two years after the war, he resigned from the University and moved between Ireland, Oxford and Cambridge.

Wittgenstein’s philosophy was divided into two periods: the first, called Wittgenstein I, is the period before 1929, which corresponds to the “Logical-Philosophical Treaty”, and the enormous influence it exerted on the Vienna Circle. The second, called Wittgenstein II, is the period after 1930 and corresponds to the “Philosophical Investigations”, which exerted great influence on analytical philosophy in general, and on the Cambridge and Oxford schools.

Ludwig Wittgenstein died in Cambridge, England, on April 29, 1951.

Works of Ludwig Wittgenstein

1. Tractatus logico-philosophicus (Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung).

2. Philosophical research (1953).

3. Notes on the foundations of mathematics (1953).

4. Blue and brown notebooks (1958).

5. Philosophical diary of 1914-16 (1961).

6. Philosophical observations (1965).

7. Ethics readings (1965).

8. Readings and conversations about aesthetics, psychology and religious beliefs (1966).

9. On certainty (1969).

Philosophical Thought of Ludwig Wittgenstein

When it comes to Ludwig’s philosophical and logical work, two very limited periods can be seen within the framework of his most important literary creations.

There is talk of a first and second Wittgenstein. The first based on his novel book, the only one he saw in life, the Tractatus logical-philosophicus , where Ludwig believed he resolved all questions of philosophy. In this period all his logical thinking is manifested in a work preceded by several small deliveries addressed to his teachers, Notes on logic for Russell (1913), and a compendium of Wittgenstein’s philosophical investigations that he called Notes dictated to Moore (1914).

But, after several years of retirement in which he even gave up family inheritance and simplified his lifestyle, Ludwig returns with a new impetus and, of course, with new teachings , which he would record in his research published after his death. . The second Wittgenstein is thus known.

First Wittgenstein: Tractatus logico-philosophicus

The essay “An event of the utmost importance in the philosophical world”, as well expressed in the prologue by his teacher Bertrand Russell, is considered the key work of the philosopher Ludwig. It is the result of a reflective period in the life of the Viennese, in a context as convulsive as that of war.

Ludwig voluntarily enlisted in his country’s troops when the conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia broke out on July 28, 1914, in an attempt to measure his courage and find new meaning in life.

Between 1914 and 1916, countless correspondence with his guides Bertrand Russell, George Edward Moore and economist John Maynard Keynes laid the foundation of his philosophical treatise, in which the first Wittgenstein confronts the central approaches of philosophy: world, thought and language .

Ludwig resolves that thought represents the world as a proposition with meaning and, considering that both share the same form from the logical point of view, they can become images of the facts. In other words, it is about showing the living form of what language cannot express with meanings.

Although it is a text of a complex nature, it does not present any thesis as such and its author did not consider it a work of teaching. Ludwig struggled to present his thinking with 7 main maxims, from least to greatest in importance:

- The world is all that happens

- What happens, the facts, are “states of affairs.”

- A logical representation of facts is a thought.

- A thought is a proposition with meaning.

- A proposition is a function of truth of elementary propositions, these being functions of truth in itself.

- The general form of a function of truth.

- What we cannot talk about must be silent.

Second Wittgenstein: Philosophical Investigations

A second era illustrated a Ludwig Wittgenstein with a much more challenging spirit, even with his own material. He was a thinker, now trained to impart knowledge after his preparation at the Vienna School of Teaching.

The Ludwig teacher of rural schools in Lower Austria shook the academy of philosophy, pointing to the great traditional questions of it as ghost problems that appeared as a result of a misunderstanding of the logic of language. Yes, the interpretation is that Ludwig was contradicting himself in this new stage with respect to his first resolutions.

He tried to deny the existence of two aspects; what can be expressed with language and what must be silent for not getting form in it. This position could well be rooted in the frustration that he personally dragged after his participation in the First World War, an experience he was certain of getting strengthened and renewed, but that was not the case.

Ludwig then concentrated on his teaching profession with a completely different perspective, which gave more opportunity to the pragmatic origin of language. What is language for and what do we use it for?

His return to the academy, also claimed by his colleagues, went big. In 1929 he obtained a doctorate at Cambridge by submitting his Tractatus for evaluation with a method to analyze totally different language, leaving behind that logical atomism that he presented in his famous war work initially, and giving way to a more ordinary approach to language. With this turn, the so-called “second Wittgenstein” was officially presented.

This era was considered one of the most prolific in philosophical contributions for Ludwig, but the main text that is collected from his thoughts in the 1930s are the philosophical investigations , in which he assures that the true meaning of words and propositions in his correct sense, they are in their use (Gebrauch) immersed in language.

What would be the criteria to call the correct use of a word or proposition? Wittgenstein limits him to the context to which he belongs, and thus draws a whole different framework for language as he presented it in his first period. Enter what Ludwig called the language game or Sprachspiel . A sentence will only sound absurd if it is used out of context, outside its own field, which will always be a projection of the life and experience of those who are using it.

With these new concepts , the universal aspect of Wittgenstein’s language is also consolidated, highlighting that it must be governed by its own common rules in a collective. It banishes the possibility of a private language and keeps the purpose of philosophy linked to the service of showing through the word.